Sustainability considerations in the Riksbank’s asset management

Published: 25 January 2023

The Riksbank’s gold and foreign exchange reserves account for a large part of the Riksbank’s total assets and are worth approximately SEK 560 billion. When selecting assets for the foreign exchange reserves, the Riksbank takes sustainability into account as far as it can without affecting its ability to carry out its main tasks.

During the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 and 2021, the Riksbank increased its holdings of assets in the form of securities denominated in Swedish kronor in order to support the economy and to attain the inflation target.[14] The purchases included covered bonds (mortgage bonds), municipal bonds, government bonds, treasury bills and corporate debt securities (corporate bonds and commercial paper). The Riksbank also purchased government bonds for monetary policy purposes between 2015 and 2020. In 2022, the Riksbank continued to purchase securities denominated in Swedish kronor, albeit to a lesser extent, and holdings declined due to redemptions. At the turn of 2022/2023, purchases of Swedish securities ceased and holdings are thus set to decline as they mature.[15] On 31 December 2022, the Riksbank’s holdings in Swedish securities amounted to approximately SEK 820 billion. Among other things, in its Swedish asset purchases, the Riksbank has purchased bonds issued by Swedish non-financial corporations and has taken sustainability into account in order to manage the financial risks on its balance sheet.

Sustainability considerations in the foreign exchange reserves

The gold and foreign exchange reserves exist to enable the Riksbank to offer banks liquidity support in foreign currencies in times of financial stress and to enable the Riksbank to carry out currency interventions. The reserves are also used to deal with some of Sweden's commitments to the IMF.[16] As a result of the new Sveriges Riksbank Act, which entered into force on 1 January 2023, loans to the IMF are to be made via the Swedish National Debt Office. These assignments are used as a starting point when the Riksbank is determining the currency distribution and which assets need to be held in the foreign exchange reserves.

In order for the Riksbank to have a good level of preparedness, the foreign exchange reserves consist mainly of bonds issued by governments with high credit ratings, as such assets can be quickly converted into liquid funds. The Riksbank holds assets primarily in US dollars and euros, but also in British pounds and Norwegian and Danish kroner. In order to spread the risks and increase the return, the Riksbank has also chosen to hold a small part of its foreign exchange reserves in Australian and Canadian dollars.

Since 2019, the Riksbank’s financial risk and investment policy has stated that the Riksbank shall take sustainability into account in the selection of assets in the foreign exchange reserves. We do this by taking the carbon footprint into account when deciding on the composition of the foreign exchange reserves. We try, as far as possible given the purpose of the foreign exchange reserves, to limit the overall carbon footprint without significantly reducing the return or increasing the risk. This has meant that the Riksbank has made some adjustments to its holdings in recent years.[17] In 2019, the Riksbank decided to invest only in Australian states and Canadian provinces that have the same or lower carbon footprints than the country’s total carbon footprint. The Riksbank also makes an assessment based on sustainability factors before including new assets in the foreign exchange reserves.

The Riksbank reports the carbon footprint of the assets in the foreign exchange reserves

Since 2022, the Riksbank reports the carbon footprint of its holdings of bonds in the foreign exchange reserves.[18] The carbon footprint is updated annually and reported on the Riksbank’s website; see Carbon footprint of the Riksbank’s foreign exchange reserves. This is part of the process of calculating and reporting climate-related risks on the balance sheet and helps to promote transparency regarding climate-related information.

The Riksbank reports the carbon footprint as an intensity measure, which, in this case, means that countries and regions’ greenhouse gas emissions are placed in relation to their output. This makes it possible to compare the footprint of different countries and regions. An Economic Commentary explains why the Riksbank uses this particular measure.[19] See E. Brattström and R. Gajic (2022). The carbon footprint of the assets in the Riksbank’s foreign exchange reserves, Economic Commentaries, No. 4, Sveriges Riksbank.

In the calculation, the carbon intensity of each asset is weighted against its share in the foreign exchange reserve (weighted average carbon intensity or WACI). Figure 1 shows the carbon footprint as of 31 December 2022, which amounted to 264 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents[20] Carbon dioxide equivalents are a measure whereby the warming potential of different greenhouse gases is translated into a standard unit. This is because emissions of a certain amount of greenhouse gas have different effects on the climate. per million dollars of GDP.

The bonds included in the calculations represent approximately 73 per cent of the market value of the foreign exchange reserves. The remaining 27 per cent consists of bonds issued by international organisations and state-guaranteed organisations, as well as of liquid funds in bank accounts. For these holdings, data on greenhouse gas emissions are not available or reporting is not yet sufficiently developed. Consequently, these holdings are not included in the calculations. The carbon footprint of the foreign exchange reserves has to be interpreted with some caution as the holdings that are included are given a higher weight in the calculation than if all holdings had been included.

Figure 1. Carbon footprint of the foreign exchange reserves on 31 December 2022

Figure: Carbon footprint of the foreign exchange reserves on 31 December 2022

Note. The carbon footprint is calculated for bonds in the foreign exchange reserves issued by states and regions, which represent just over 73 per cent of the foreign exchange reserves. Due to a lag in the reporting of national greenhouse gas emissions, emissions data and GDP data for 2020 are used in the calculations.

Sources: UNFCCC GHG Data Interface, OECD National Accounts Statistics and own calculations.

The size of the carbon footprint in the foreign exchange reserves depends on two things: how much we own of a country or region’s securities and their related carbon intensity. Figure 2 illustrates how the holdings in various countries and regions’ bonds contributes to the Riksbank’s carbon footprint (red bar) and how much the bonds make up of the part of the foreign exchange reserves included in the carbon footprint calculations (blue bar). For example, holdings of US government bonds (expressed as USD in the figure) account for 63 per cent of the foreign exchange reserve’s carbon footprint, while they represent 54 per cent of the basis used to calculate the carbon footprint. For the holding of government bonds in euros (expressed as EUR in the diagram), the relationship is the opposite. The assets in euros instead account for 21 per cent of the foreign exchange reserves’ carbon footprint, while the holding represents 28 per cent of the basis for calculation. The assets in USD thus have a relatively higher carbon intensity and the assets in EUR have a relatively lower carbon intensity.

Figure 2. How much different countries and regions contribute to the carbon footprint and their share of the foreign exchange reserves

Figure: How much different countries and regions contribute to the carbon footprint and their share of the foreign exchange reserves

Sources: UNFCCC GHG Data Interface, OECD National Accounts Statistics, Sveriges Riksbank and own calculations.

*The share of the foreign exchange reserves in a given country and region is calculated from the bonds that form the basis for calculating the carbon footprint

The Riksbank has taken sustainability into account in its purchases of corporate bonds

Since January 2021, the Riksbank has applied so-called norm-based negative screening when purchasing corporate bonds. This means that the Riksbank has only considered buying bonds issued by companies that are deemed to meet the principles of sustainability formulated in international standards and norms.[21] The negative screening is based on the UN Global Compact, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. These standards span the areas of human rights, working conditions, the environment and anti-corruption. This screening has been based on the assumption that it is more risky to buy bonds issued by companies that violate these principles. The aim of the screening has thus been to limit the Riksbank’s financial risks linked to sustainability.[22] A longer discussion of this can be found in a previously published Economic Commentary; see M. Andersson and M. Stenström (2021), "Sustainability considerations when purchasing corporate bonds", Economic Commentary, No. 3, Sveriges Riksbank.

Since 2021, the Riksbank has measured and reported the carbon footprint of the holdings in its corporate bond portfolio. This analysis helps us to understand the climate-related risks in the Riksbank’s operations. However, in the absence of comprehensive carbon data, it is difficult to reliably measure and manage these risks. Therefore, in order to take climate-related financial risks into account when purchasing corporate bonds, the Riksbank introduced a new purchase criterion in 2022.[23] The decision was taken in conjunction with the monetary policy meeting in June 2022 and can be read about in Annex B to the minutes. In short, this meant that the Riksbank only offered to purchase bonds issued by companies that reported their annual direct emissions (scope 1) and indirect emissions (scope 2)[24] Emissions are divided into different categories, where scope 1 refers to direct emissions, i.e. emissions from sources owned or controlled by the company, and scope 2 refers to indirect emissions, such as emissions from electricity purchased by the company. in accordance with the TCFD recommendations[25] In turn, these recommendations are based on the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a global reporting standard used by companies to quantify, evaluate and manage greenhouse gas emissions. (see more on the TCFD in section 2.2).

The carbon footprint of the Riksbank’s holdings of corporate bonds

When the Riksbank reports the carbon footprint of its holdings of corporate bonds, weighted average carbon intensity is used, just as for the foreign exchange reserves.[26] The carbon footprint is updated quarterly; see the Riksbank’s website on the Carbon footprint of the holdings of corporate bonds. For more information on how the carbon footprint is calculated, see J. Blixt, E. Brattström and M. Ferlin (2021), "Sustainability reporting - need for greater standardisation and transparency", Economic Commentaries, No. 4, Sveriges Riksbank. On 31 December 2022, the carbon footprint totalled 99 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents per million US dollars of revenue. The carbon footprint is calculated using both the companies’ reported greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 and quantitative estimates of emissions made by the company Sustainalytics. As the calculations are partly based on estimates, the carbon footprint of the Riksbank’s holdings of corporate bonds should be seen more as an indication than a precise calculation.

FACTS - The Riksbank collects statistics on the issuance of green bonds in Sweden

There is currently no single definition of green bonds, but there are two international frameworks: the Green Bond Principles (GBP)[28] See Green Bond Principles (GBP). and the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), better known as the Climate Bonds Standard (CBS).[29] See Climate Bonds Standard (CBS). The EU is continuously working to develop and quality assure the frameworks and definitions, for example so that external auditors ensure that the green bond meets the requirements set out.

The issuance of green bonds does not imply that the activities of the companies or governments issuing green bonds are sustainable in their entirety. The real estate company Vasakronan was the first Swedish company to issue a green bond in 2013 and the first green Swedish government bond was issued in 2020.[27] See M. Ferlin and V. Sternbeck Fryxell (2020), “Green bonds – big in Sweden and with the potential to grow”, Economic Commentaries, No. 12, Sveriges Riksbank.

Non-financial corporations are the largest issuers of green bonds

Since 2021, around 90 major Swedish bond issuers have been submitting monthly data to the Riksbank’s securities database to indicate whether their issued securities are green or not. Of the reporting entities, around 40 issue green bonds that comply with the principles of one of the frameworks mentioned above. Non-financial corporations are the largest issuers of green bonds; see Figure 3. Most green bonds issued in Sweden are in Swedish kronor. Green bonds have grown strongly in recent years and now account for around six per cent of the value of all bonds issued.

Figure 3. Issuers of green bonds, by sector

Figure: Issuers of green bonds, by sector

Figure 3 describes which Swedish sectors issue green bonds. It shows that non-financial corporations are the largest issuers of green bonds, although the MFI sector (mainly banks) has increased most since February 2021.

Note. MFIs refer to monetary financial institutions, such as banks and housing credit institutions.

Source: Statistics Sweden (SVDB).

Investment funds, insurance corporations and pension funds are the largest holders

Of the green bonds issued in Swedish kronor, foreign investors own about one-fifth, while those issued in foreign currency are overwhelmingly owned by foreign investors.

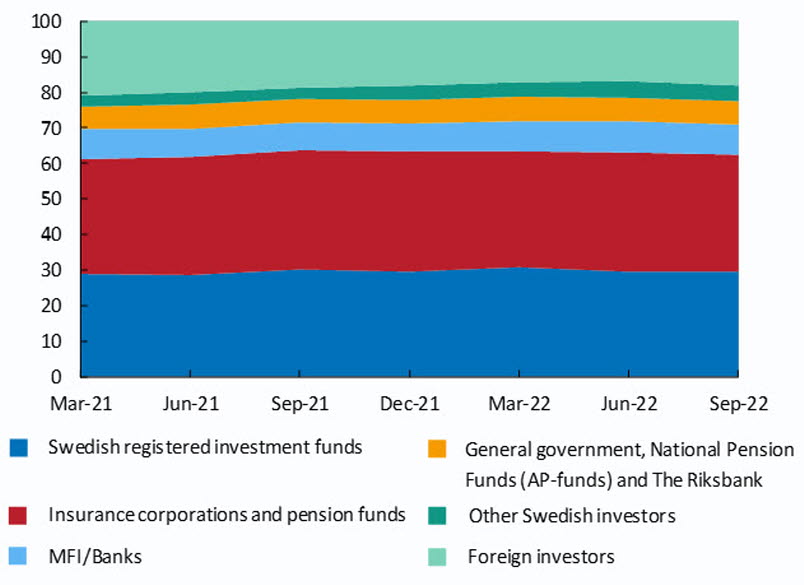

Among Swedish investors, green bonds are mainly held by investment funds, insurance corporations and pension funds. Together, their holdings account for about three-fifths of green bonds in Swedish kronor; see Figure 4. They also account for a large share of holdings of Swedish interest-bearing securities in total. However, their holdings of green bonds are also relatively higher than the green holdings of other sectors. The fact that the general government sector, the Riksbank and the National Pension Funds (AP funds) do not own such a large share of green bonds is due to the fact that large parts of their securities holdings consist of government bonds and covered bonds. As Figure 3 shows, the share of green bonds among these is relatively small.

Figure 4 shows who owns green bonds issued in Swedish kronor. Insurance corporations and pension funds, together with Swedish-registered investment funds, are the largest categories of owners and together own around 60 per cent of the outstanding bonds. Foreign investors own about 20 per cent. The ownership structure was relatively stable during the years 2021 and 2022.

Note. Issued by Swedish issuers and with SEK as issuing currency.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and the Riksbank (SVDB and VINN).January 2023

Download PDF